When working with differential equations, usually the goal is to find a solution. In other words, we want to find a function (or functions) that satisfies the differential equation. The technique we use to find these solutions varies, depending on the form of the differential equation with which we are working. Second-order differential equations have several important characteristics that can help us determine which solution method to use. In this section, we examine some of these characteristics and the associated terminology.

Consider the second-order differential equation

Notice that \(y\) and its derivatives appear in a relatively simple form. They are multiplied by functions of \(x\), but are not raised to any powers themselves, nor are they multiplied together. As discussed in previously, first-order equations with similar characteristics are said to be linear. The same is true of second-order equations. Also note that all the terms in this differential equation involve either \(y\) or one of its derivatives. There are no terms involving only functions of \(x\). Equations like this, in which every term contains \(y\) or one of its derivatives, are called homogeneous.

Not all differential equations are homogeneous. Consider the differential equation

The \(x^2\) term on the right side of the equal sign does not contain \(y\) or any of its derivatives. Therefore, this differential equation is nonhomogeneous.

A second-order differential equation is linear if it can be written in the form

where \(a_(x), a_(x), a_(x),\) and \(r(x)\) are real-valued functions and \(a_(x)\) is not identically zero. If \(r(x) \equiv 0\)—in other words, if \(r(x)=0\) for every value of \(x\)—the equation is said to be a homogeneous linear equation. If \(r(x) \neq 0\) for some value of \(x,\) the equation is said to be a nonhomogeneous linear equation.

In linear differential equations, \(y\) and its derivatives can be raised only to the first power and they may not be multiplied by one another. Terms involving \(y^2\) or \(\sqrt\) make the equation nonlinear. Functions of \(y\) and its derivatives, such as \(\sin y\) or \(e^\), are similarly prohibited in linear differential equations.

Note that equations may not always be given in standard form (the form shown in the definition). It can be helpful to rewrite them in that form to decide whether they are linear, or whether a linear equation is homogeneous.

Classify each of the following equations as linear or nonlinear. If the equation is linear, determine further whether it is homogeneous or nonhomogeneous.

Classify each of the following equations as linear or nonlinear. If the equation is linear, determine further whether it is homogeneous or nonhomogeneous.

Write the equation in standard form (Equation \ref) if necessary. Check for powers or functions of \(y\) and its derivatives.

Answer a

Answer b

Later in this section, we will see some techniques for solving specific types of differential equations. Before we get to that, however, let’s get a feel for how solutions to linear differential equations behave. In many cases, solving differential equations depends on making educated guesses about what the solution might look like. Knowing how various types of solutions behave will be helpful.

Consider the linear, homogeneous differential equation

Looking at this equation, notice that the coefficient functions are polynomials, with higher powers of \(x\) associated with higher-order derivatives of \(y\). Show that \(y=x^3\) is a solution to this differential equation.

Let \(y=x^3.\) Then \(y'=3x^2\) and \(y''=6x.\) Substituting into the differential equation, we see that

Show that \(y=2x^2\) is a solution to the differential equation

Hint

Calculate the derivatives and substitute them into the differential equation.

Answer

This requires calculating \(y'\) and \(y''\).

\[y' = \dfrac = 4x \nonumber \]

Inserting these derivatives along with \(y=2x^2\) into Equation \ref.

\[\begin \dfracx^2y''-xy'+y &\overset 0 \\[4pt] \dfracx^2(4) - x (4x) + 2x^2 &\overset 0 \\[4pt] 2x^2 - 4x^2 + 2x^2 &\overset 0 \end \nonumber \]

Yes, this is a solution to the differential equation in Equation \ref.

Although simply finding any solution to a differential equation is important, mathematicians and engineers often want to go beyond finding one solution to a differential equation to finding all solutions to a differential equation. In other words, we want to find a general solution. Just as with first-order differential equations, a general solution (or family of solutions) gives the entire set of solutions to a differential equation. An important difference between first-order and second-order equations is that, with second-order equations, we typically need to find two different solutions to the equation to find the general solution. If we find two solutions, then any linear combination of these solutions is also a solution. We state this fact as the following theorem.

If \(y_1(x)\) and \(y_2(x)\) are solutions to a linear homogeneous differential equation, then the function

where \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are constants, is also a solution.

The proof of this superposition principle theorem is left as an exercise.

Consider the differential equation

Given that \(e^\) and \(e^\) are solutions to this differential equation, show that \(4e^+e^\) is a solution.

Although this can be done through a simple application of the Superposition principle (Equation \ref), but we can also confirm it is a solution via an approach like in Example \(\PageIndex\). We have

Thus, \(y(x)=4e^+e^\) is a solution.

Consider the differential equation

Given that \(e^\) and \(e^\) are solutions to this differential equation, show that \(3e^+6e^\) is a solution.

Hint

Differentiate the function and substitute into the differential equation.

Answer

Although this can be a simple application of the Superposition principle (Equation \ref), we can also set through it like in Example \(\PageIndex\). We have

Thus, \(3e^+6e^\) is a solution to the differential equation

Unfortunately, to find the general solution to a second-order differential equation, it is not enough to find any two solutions and then combine them. Consider the differential equation

Both \(e^\) and \(2e^\) are solutions (you can check this). However,

is not the general solution. This expression does not account for all solutions to the differential equation. In particular, it fails to account for the function \(e^,\) which is also a solution to the differential equation. It turns out that to find the general solution to a second-order differential equation, we must find two linearly independent solutions. We define that terminology here.

A set of functions \(f_1(x),\, f_2(x), \ldots ,f_n(x)\) is said to be linearly dependent if there are constants \(c_1,\, c_2, \ldots c_n,\), not all zero, such that

\[c_1f_1(x)+c_2f_2(x)+ \cdots +c_nf_n(x)=0 \nonumber \]

for all \(x\) over the interval of interest. A set of functions that is not linearly dependent is said to be linearly independent.

In this chapter, we usually test sets of only two functions for linear independence, which allows us to simplify this definition. From a practical perspective, we see that two functions are linearly dependent if either one of them is identically zero or if they are constant multiples of each other.

First we show that if the functions meet the conditions given previously, then they are linearly dependent. If one of the functions is identically zero—say, \(f_2(x) \equiv 0\)—then choose \(c_1=0\) and \(c_2=1,\) and the condition for linear dependence is satisfied. If, on the other hand, neither \(f_1(x)\) nor \(f_2(x)\) is identically zero, but \(f_1(x)=Cf_2(x)\) for some constant \(C,\) then choose \(c_1=C\) and \(c_2=-1,\) and again, the condition is satisfied.

Next, we show that if two functions are linearly dependent, then either one is identically zero or they are constant multiples of one another. Assume \(f_1(x)\) and \(f_2(x)\) are linearly independent. Then, there are constants, \(c_1\) and \(c_2,\) not both zero, such that

for all \(x\) over the interval of interest. Then,

Now, since we stated that \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) can’t both be zero, assume \(c_2 \neq 0.\) Then, there are two cases: either \(c_1=0\) or \(c_1\neq 0.\) If \(c_1=0,\) then

so one of the functions is identically zero. Now suppose \(c_1 \neq 0.\) Then,

\[f_1(x)=\left(- \dfrac\right)f_2(x) \nonumber \]

and we see that the functions are constant multiples of one another.

Two functions, \(f_1(x)\) and \(f_2(x),\) are said to be linearly dependent if either one of them is identically zero or if \(f_1(x)=Cf_2(x)\) for some constant \(C\) and for all \(x\) over the interval of interest. Functions that are not linearly dependent are said to be linearly independent.

Determine whether the following pairs of functions are linearly dependent or linearly independent.

Solution

Determine whether the following pairs of functions are linearly dependent or linearly independent: \(f_1(x)=e^\) and \(f_2(x)=3e^.\)

Hint

Are the functions constant multiples of one another?

Answer

If we are able to find two linearly independent solutions to a second-order differential equation, then we can combine them to find the general solution. This result is formally stated in the following theorem.

If \(y_1(x)\) and \(y_2(x)\) are linearly independent solutions to a second-order, linear, homogeneous differential equation, then the general solution is given by

where \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are constants.

When we say a family of functions is the general solution to a differential equation, we mean that

If we can find two linearly independent solutions to a second order differential equation, we have, effectively, found all solutions to the second order differential equation—quite a remarkable statement. The proof of this theorem is beyond the scope of this text.

If \(y_1(t)=e^\) and \(y_2(t)=e^\) are solutions to \(y''-9y=0,\) what is the general solution?

Solution

Note that \(y_1\) and \(y_2\) are not constant multiples of one another, so they are linearly independent. Then, the general solution to the differential equation is

If \(y_1(x)=e^\) and \(y_2(x)=xe^\) are solutions to \(y''-6y'+9y=0,\) what is the general solution?

Hint

Check for linear independence first.

Answer

Now that we have a better feel for linear differential equations, we are going to concentrate on solving second-order equations of the form

where \(a, b,\) and \(c\) are constants.

Since all the coefficients are constants, the solutions are probably going to be functions with derivatives that are constant multiples of themselves. We need all the terms to cancel out, and if taking a derivative introduces a term that is not a constant multiple of the original function, it is difficult to see how that term cancels out. Exponential functions have derivatives that are constant multiples of the original function, so let’s see what happens when we try a solution of the form \(y(x)=e^< \lambda x>\), where \(\lambda\) (the lowercase Greek letter lambda) is some constant.

If \(y(x)=e^< \lambda x>\), then \(y'(x)= \lambda e^< \lambda x>\) and \(y''= \lambda^2 e^< \lambda x>.\) Substituting these expressions into Equation \ref, we get

Since \(e^<\lambda x>\) is never zero, this expression can be equal to zero for all \(x\) only if

\[a\lambda^2+b\lambda +c=0. \nonumber \]

We call this the characteristic equation of the differential equation.

The characteristic equation of the second order differential equation \(ay''+by'+cy=0\) is

\[a\lambda^2+b\lambda +c=0. \nonumber \]

The characteristic equation is very important in finding solutions to differential equations of this form. We can solve the characteristic equation either by factoring or by using the quadratic formula

This gives three cases. The characteristic equation has

We consider each of these cases separately.

If the characteristic equation has distinct real roots \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\), then \(e^<\lambda_1x>\) and \(e^<\lambda_2x>\) are linearly independent solutions to Example \ref, and the general solution is given by

where \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are constants.

For example, the differential equation \(y''+9y'+14y=0\) has the associated characteristic equation \(\lambda^2+9\lambda+14=0.\) This factors into \((\lambda +2)(\lambda +7)=0,\) which has roots \(\lambda_1=-2\) and \(\lambda_2=-7.\) Therefore, the general solution to this differential equation is

Things are a little more complicated if the characteristic equation has a repeated real root, \(\lambda\). In this case, we know \(e^<\lambda x>\) is a solution to Equation \ref, but it is only one solution and we need two linearly independent solutions to determine the general solution. We might be tempted to try a function of the form \(ke^<\lambda x>,\) where \(k\) is some constant, but it would not be linearly independent of \(e^<\lambda x>.\) Therefore, let’s try \(xe^<\lambda x>\) as the second solution. First, note that by the quadratic formula,

But, \(\lambda\) is a repeated root, so the discriminate (\(b^2-4ac\)) is zero and \(\lambda = \frac\). Thus, if \(y=xe^<\lambda x>\), we have

Substituting both expressions into Equation \ref, we see that

This shows that \(xe^<\lambda x>\) is a solution to Equation \ref. Since \(e^<\lambda x>\) and \(xe^<\lambda x>\) are linearly independent, when the characteristic equation has a repeated root \(\lambda \), the general solution to Equation \ref is given by

where \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are constants.

For example, the differential equation \(y''+12y'+36y=0\) has the associated characteristic equation

\[\lambda^2+12 \lambda +36=0.\nonumber \]

This factors into \((\lambda +6)^2=0,\) which has a repeated root \(\lambda =-6\). Therefore, the general solution to this differential equation is

The third case we must consider is when \(b^2-4ac \) to find the roots, which take the form \(\lambda_1= \alpha + \beta i \) and \(\lambda _2=\alpha -\beta i.\) The complex number \( \alpha +\beta i\) is called the conjugate of \( \alpha -\beta i\). Thus, we see that when the discriminate \(b^2-4ac\) is negative, the roots of our characteristic equation are always complex conjugates.

This creates a little bit of a problem for us. If we follow the same process we used for distinct real roots—using the roots of the characteristic equation as the coefficients in the exponents of exponential functions—we get the functions \(e^<(\alpha + \beta i)x>\) and \(e^<(\alpha - \beta i)x>\) as our solutions. However, there are problems with this approach. First, these functions take on complex (imaginary) values, and a complete discussion of such functions is beyond the scope of this text. Second, even if we were comfortable with complex-value functions, in this course we do not address the idea of a derivative for such functions. So, if possible, we’d like to find two linearly independent real-value solutions to the differential equation. For purposes of this development, we are going to manipulate and differentiate the functions \(e^<(\alpha + \beta i)x>\) and \(e^<(\alpha - \beta i)x>\) as if they were real-value functions. For these particular functions, this approach is valid mathematically, but be aware that there are other instances when complex-value functions do not follow the same rules as real-value functions. Those of you interested in a more in-depth discussion of complex-value functions should consult a complex analysis text.

Based on the roots \(\alpha \pm \beta i\) of the characteristic equation, the functions \(e^<(\alpha + \beta i)x>\) and \(e^<(\alpha - \beta i)x>\) are linearly independent solutions to the differential equation and the general solution is given by

Using some smart choices for \(c_1\) and \(c_2\), and a little bit of algebraic manipulation, we can find two linearly independent, real-value solutions to Equation \ref and express our general solution in those terms.

We encountered exponential functions with complex exponents earlier. One of the key tools we used to express these exponential functions in terms of sines and cosines was Euler’s formula, which tells us that

for all real numbers \(\theta \).

Going back to the general solution, we have

Applying Euler’s formula (Equation \ref) together with the identities \(\cos(-x)=\cos x\) and \(\sin(-x)=- \sin x,\) we get

\[\begin y(x) &=e^[c_1(\cos \beta x+i \sin \beta x)+c_2(\cos(- \beta x)+i \sin(- \beta x))] \nonumber \\[4pt] &=e^[(c_1+c_2)\cos \beta x+(c_1-c_2)i \sin \beta x]. \label\end \]

Now, if we choose \(c_1=c_2= \frac,\) the second term is zero and we get

\[y(x)=e^ \cos \beta x \nonumber \]

as a real-value solution to Equation \ref. Similarly, if we choose \(c_1=−\frac\) and \(c_2=\frac\), the first term of Equation \ref is zero and we get

\[y(x)=e^ \sin \beta x \nonumber \]

as a second, linearly independent, real-value solution to Equation \ref.

Based on this, we see that if the characteristic equation has complex conjugate roots \(\alpha \pm \beta i,\) then the general solution to Equation \ref is given by

\[\begin y(x) &=c_1e^ \cos \beta x+c_2e^ \sin \beta x \\[4pt] &=e^(c_1 \cos \beta x+c_2 \sin \beta x),\end\]

where \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are constants.

For example, the differential equation \(y''-2y'+5y=0\) has the associated characteristic equation \(\lambda ^2-2 \lambda +5=0.\) By the quadratic formula, the roots of the characteristic equation are \(1\pm 2i.\) Therefore, the general solution to this differential equation is

\[y(x)=e^(c_1 \cos 2x+c_2 \sin 2x).\nonumber \]

We can solve second-order, linear, homogeneous differential equations with constant coefficients by finding the roots of the associated characteristic equation. The form of the general solution varies, depending on whether the characteristic equation has distinct, real roots; a single, repeated real root; or complex conjugate roots. The three cases are summarized in Table \(\PageIndex\).

| Characteristic Equation Roots | General Solution to the Differential Equation |

|---|---|

| Distinct real roots, \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\) | \(y(x)=c_1e^<\lambda_1x>+c_2e^<\lambda_2x>\) |

| A repeated real root, \(\lambda \) | \(y(x)=c_1e^<\lambda x>+c_2xe^<\lambda x>\) |

| Complex conjugate roots \(\alpha \pm \beta i\) | \(y(x)=e^(c_1 \cos \beta x+c_2 \sin \beta x)\) |

Find the general solution to the following differential equations. Give your answers as functions of \(x\).

Note that all these equations are already given in standard form (step 1).

Find the general solution to the following differential equations:

Find the roots of the characteristic equation.

Answer a

\(y(x)=e^x(c_1 \cos 3x+c_2 \sin 3x)\)

Answer b

So far, we have been finding general solutions to differential equations. However, differential equations are often used to describe physical systems, and the person studying that physical system usually knows something about the state of that system at one or more points in time. For example, if a constant-coefficient differential equation is representing how far a motorcycle shock absorber is compressed, we might know that the rider is sitting still on his motorcycle at the start of a race, time \(t=t_0.\) This means the system is at equilibrium, so \(y(t_0)=0,\) and the compression of the shock absorber is not changing, so \(y'(t_0)=0.\) With these two initial conditions and the general solution to the differential equation, we can find the specific solution to the differential equation that satisfies both initial conditions. This process is known as solving an initial-value problem. (Recall that we discussed initial-value problems in Introduction to Differential Equations.) Note that second-order equations have two arbitrary constants in the general solution, and therefore we require two initial conditions to find the solution to the initial-value problem.

Sometimes we know the condition of the system at two different times. For example, we might know \(y(t_0)=y_0\) and \(y(t_1)=y_1.\)These conditions are called boundary conditions, and finding the solution to the differential equation that satisfies the boundary conditions is called solving a boundary-value problem.

Mathematicians, scientists, and engineers are interested in understanding the conditions under which an initial-value problem or a boundary-value problem has a unique solution. Although a complete treatment of this topic is beyond the scope of this text, it is useful to know that, within the context of constant-coefficient, second-order equations, initial-value problems are guaranteed to have a unique solution as long as two initial conditions are provided. Boundary-value problems, however, are not as well behaved. Even when two boundary conditions are known, we may encounter boundary-value problems with unique solutions, many solutions, or no solution at all.

Solve the following initial-value problem: \(y''+3y'-4y=0, \, y(0)=1,\, y'(0)=-9.\)

We already solved this differential equation in Example 17.6a. and found the general solution to be

When \(x=0,\) we have \(y(0)=c_1+c_2\) and \(y'(0)=-4c_1+c_2.\) Applying the initial conditions, we have

Then \(c_1=1-c_2.\) Substituting this expression into the second equation, we see that

\[\begin -4(1-c_2)+c_2 &= -9 \\[4pt] -4+4c_2+c_2 &=-9 \\[4pt] 5c_2 &=-5 \\[4pt] c_2 &=-1. \end\]

So, \(c_1=2\) and the solution to the initial-value problem is

Solve the initial-value problem \(y''-3y'-10y=0, \quad y(0)=0, \; y'(0)=7.\)

Hint

Use the initial conditions to determine values for \(c_1\) and \(c_2\).

Answer

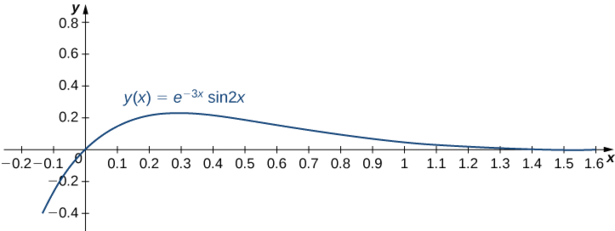

Solve the following initial-value problem and graph the solution:

\[y''+6y'+13y=0, \quad y(0)=0, \; y'(0)=2\nonumber \]

We already solved this differential equation in Example \(\PageIndex\). and found the general solution to be

\[y(x)=e^(c_1 \cos 2x+c_2 \sin 2x).\nonumber \]

\[y'(x)=e^(-2c_1 \sin 2x+2c_2 \cos 2x)-3e^(c_1 \cos 2x+c_2 \sin 2x). \nonumber \]

When \(x=0,\) we have \(y(0)=c_1\) and \(y'(0)=2c_2-3c_1\). Applying the initial conditions, we obtain

Therefore, \(c_1=0, \, c_2=1,\) and the solution to the initial value problem is shown in the following graph.

Solve the following initial-value problem and graph the solution: \(y''-2y'+10y=0, \quad y(0)=2, \; y'(0)=-1\)

Hint

Use the initial conditions to determine values for \(c_1\) and \(c_2.\)

Answer

\[y(x)=e^(2 \cos 3x - \sin 3x) \nonumber \]

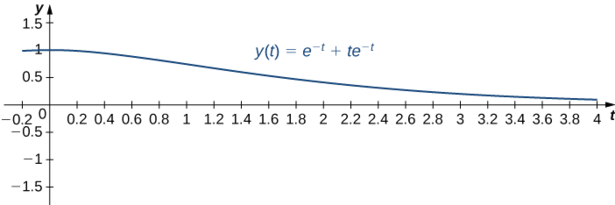

The following initial-value problem models the position of an object with mass attached to a spring. Spring-mass systems are examined in detail in Applications. The solution to the differential equation gives the position of the mass with respect to a neutral (equilibrium) position (in meters) at any given time. (Note that for spring-mass systems of this type, it is customary to define the downward direction as positive.)

\[y''+2y'+y=0, \quad y(0)=1, \; y'(0)=0 \nonumber \]

Solve the initial-value problem and graph the solution. What is the position of the mass at time \(t=2\) sec? How fast is the mass moving at time \(t=1\) sec? In what direction?

In Example Example \(\PageIndex\). we found the general solution to this differential equation to be

When \(t=0,\) we have \(y(0)=c_1\) and \(y'(0)=c_1+c_2.\) Applying the initial conditions, we obtain

\[c_1=1 \\ -c_1+c_2=0. \nonumber \]

Thus, \(c_1=1, c_2=1,\) and the solution to the initial value problem is

This solution is represented in the following graph. At time \(t=2,\) the mass is at position \(y(2)=e^+2e^=3e^ \approx 0.406\) m below equilibrium.

To calculate the velocity at time \(t=1,\) we need to find the derivative. We have \(y(t)=e^+te^,\) so

Then \(y'(1)=-e^ \approx -0.3679\). At time \(t=1,\) the mass is moving upward at \(0.3679\) m/sec.

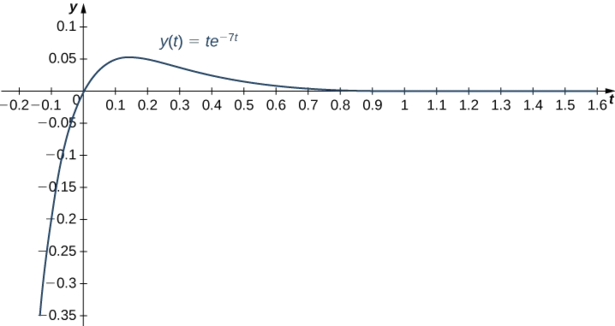

Suppose the following initial-value problem models the position (in feet) of a mass in a spring-mass system at any given time. Solve the initial-value problem and graph the solution. What is the position of the mass at time \(t=0.3\) sec? How fast is it moving at time \(t=0.1\) sec? In what direction?

\[y''+14y'+49y=0, \quad y(0)=0, \; y'(0)=1 \nonumber \]

Hint

Use the initial conditions to determine values for \(c_1\) and \(c_2\).

Answer

At time \(t=0.3, \; y(0.3)=0.3e^ <(-7^<\ast>0.3)>=0.3e^ \approx 0.0367. \) The mass is \(0.0367\)ft below equilibrium. At time \(t=0.1, \; y'(0.1)=0.3e^ \approx 0.1490.\) The mass is moving downward at a speed of \(0.1490\) ft/sec.

In Example 17.6f. we solved the differential equation \(y''+16y=0\) and found the general solution to be \(y(t)=c_1 \cos 4t+c_2 \sin 4t.\) If possible, solve the boundary-value problem if the boundary conditions are the following:

\[y(x)=c_1 \cos 4t+c_2 \sin 4t. \nonumber \]

boundary conditions the conditions that give the state of a system at different times, such as the position of a spring-mass system at two different times boundary-value problem a differential equation with associated boundary conditions characteristic equation the equation \(aλ^2+bλ+c=0\) for the differential equation \(ay″+by′+cy=0\) homogeneous linear equation a second-order differential equation that can be written in the form \(a_2(x)y″+a_1(x)y′+a_0(x)y=r(x)\), but \(r(x)=0\) for every value of \(x\) nonhomogeneous linear equation a second-order differential equation that can be written in the form \(a_2(x)y″+a_1(x)y′+a_0(x)y=r(x)\), but \(r(x)≠0\) for some value of \(x\) linearly dependent a set of functions \(f_1(x),\,f_2(x),\,…,\,f_n(x)\) for whichthere are constants \(c_1,\,c_2,\,…,\,c_n\), not all zero, such that \(c_1f_1(x)+c_2f_2(x)+⋯+c_nf_n(x)=0\) for all \(x\) in the interval of interest linearly independent a set of functions \(f_1(x),\,f_2(x),\,…,\,f_n(x)\) for which there are no constants \(c_1,\,c_2,\,…,\,c_n\), such that \(c_1f_1(x)+c_2f_2(x)+⋯+c_nf_n(x)=0\) for all \(x\) in the interval of interest

This page titled 17.1: Second-Order Linear Equations is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Gilbert Strang & Edwin “Jed” Herman (OpenStax) via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform.